All the information contained on this website is from Jean's personal correspondence with his patrons & family,

collated by Noel and Rachael Orval.

Interview - Craft Australia, Spring 1982-83

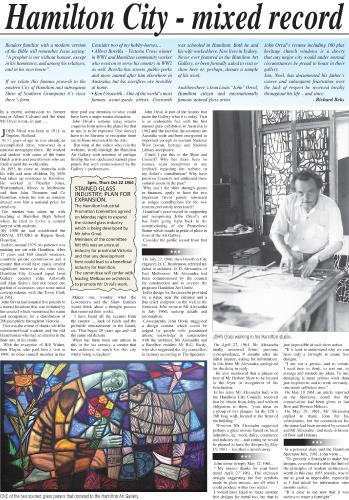

Jean Orval was born in the Netherlands in 1911, and studied stained glass

at Studio Flos in Tegelen and life drawing at Maastricht before setting up

his own studios spent in the Victorian country town of Hamilton.

From his studio there he consigned windows and other ecclesiastical art to

churches in most states of Australia. In 1962 he mounted what must have been

one of the first one man exhibitions of glass in Australia, at the Hamilton Art Gallery.

The exhibition included stained glass panels, full scale cartoons, design ideas and

technical charts and explanations, thus giving Hamilton people a rare and early

opportunity to understand the traditional art of stained glass.

However, Jean considers the late John Ashworth, then director of the Hamilton

Art Gallery to be one of the very few people who attempted to assist others to

understand and appreciate his work. Most people were indifferent and economic

survival became more and more difficult. Promises of assistance for his

decentralised business came to nothing and he left Hamilton. The Hamilton

Spectator in October of 1972 reported Jean as saying, ‘I was fed on false hope

and now I have wasted 17 years.’ The journalist on the paper remarked,

‘Exuberance mixed with bitterness and frustration produced a strange chemistry

in the man and he mixes a sense of humour with cynicism and resignation.’

Much of Jean’s cynicism and resignation has arisen from the uninformed and

unprofessional attitudes he found among the general public and with which he had to try to come to terms. He wrote recently, in his wry style, ‘It still happens. Some gentleman rang me and asked if he could come and get some information as he wanted to start on stained glass. He does blood tests, so I suppose seeing blood in a test tube brought it on him to think about making stained glass windows … Often they enquire about windows for churches. Could you glaze our Cathedral they ask? I request more information. What happens further? I never hear from them again … I suppose if they don’t make obscene phone calls they ask about church windows. They are a weird mob indeed!’

Although before coming to Australia Jean worked with the top stained glass artists in Holland, he claims he has met very few here.

There has been little encouragement or support from others in the profession to help cushion the demoralising effect of a very demanding and ill informed public. ‘I worked for five years in one studio in Holland and for about one year more in another. None of my designs would come back to be altered but here that happens very often. They ask you to make a window because they know you can do a good job, but when they receive your design they want it altered to their own taste – as if it were a design for a kitchen.’

On another occasion, writing to April Hersey of Craft Australia, Jean described difficulties he had experienced with clients who wanted a memorial window made. It was to symbolise Justice and was to match a window with a male figure which Jean had made for the same church some years before. He drew a female figure holding a sword and a set of scales. The clients decided that they did not want the female figure or the sword in the design – just the scales. ‘What good would it do to tell them that the scales on their own could symbolise one of the signs of the Zodiac, the autumn season or a grocer!’

On yet another occasion a parish priest in South Australia expressed great satisfaction with a commissioned window but complained because he could not read the inscription from both the inside and the outside.

Orval’s most pleasant memories include a Church of England minister’s wife who,

already in 1969 before it was an Australian fashion, made and served real coffee,

and one Norm McAllister of Marnoo, Victoria, who was the only man who ever

paid him before he made the design and then later insisted on paying more than

had been quoted. Jean says, ‘Most of my work here was trying to please the

people so they could pay me because if I went too far my own way they couldn’t

understand … It is the people here – or most of them anyway – who have been

and often still are dominated by the Victorian era.’

Here he is, of course, referring to his clients whom he regards as having been

hidebound by tradition and totally unaware of modern developments. He accuses

artists, on the other hand, for holding quite a different attitude towards tradition.

He believes that Australia’s contemporary glass artists, rather than understanding

tradition and then rejecting it, are just afraid of it because they

cannot understand it. Jean explained his own conception of tradition in the following way: ‘To me tradition stems from periods in which some men – sometimes artists or craftsmen – building further on what has happened before, have created something new which is still based on the creations of the past. To me “culture” is the product of the creations of tradition.’

Jean Orval is therefore well aware that to be conscious of tradition and culture means also to be burdened with it in a way that many who come to glass now are not, and also that there is a realm of experience that many of today’s glass artists do not have access to. Nor do they attempt to plumb its depths while they work strictly within the parameters of the modern “studio” glass movement. He believes they remain blissfully untouched by what has been done before and treat every studio discovery as something new. He cites an example where a recent glass artist is quoted as admiring the inventions of another in the area of ‘kiln fired three dimensional effects’ and claims that he himself experimented with these 30 or 40 years ago. He writes, ‘It was useless here, but I have experimented with glass in concrete, glass in epoxy, glass and plastic, glass and brass, glass and aluminium, glued glass, fused glass and heaven knows what else, which should at least make it clear that I was not dominated by a previous era only. I made free standing glass panels 15 to 20 years ago, but what has all that to do with a decent stained glass window?

Jean is, of course, acutely aware of the division between the crafting of a window and its aesthetic value. Like Ludwig Schaffrath, he is still of that school which considers the craftsmanship and materiality of a stained glass window to be necessary and unmentioned background elements not to be confused, as they sometimes are today, with the overall aesthetic content and quality of the work within its architectural context. He says of the younger generation, ‘They should not name any accident a stained glass panel’. We have here another instance of the attitudes and beliefs held by leading European architectural glass designers, such as Ludwig Schaffrath, who have condemned stained glass which is divorced from architecture.

Where an artist is caught in a slow transition, as Jean Orval has been, and is put in a position where his skills and gifts are unknown and unacknowledged, it is inevitable that his opinions will be strong. There is an understandable defensiveness about the European Modernist movement, which he knows and understands, and the innovations he was too early to exploit.

He wrote, with a degree of bitterness: ‘Funny that Ludwig Schaffrath comes here in 1981 to talk about the relationship between glass and architecture. I came in 1953, contacted dozens of architects and advertised as much as possible that I wanted to work together with architects because a window should be an element of an architectural whole. I doubt if anybody realised what I was talking about.’

I have quoted Jean Orval at length because I believe his candid comments are about matters and attitudes of great significance for glass artists working in Australia today. These battles are not won – despite appearances to the contrary.

By doggedly ignoring the difficulties, Jean Orval managed to produce and install a creditable range of windows throughout Victoria and South Australia. He considers two of the windows made for St Paul’s Roman Catholic Church in Mt Gambier, South Australia, after the themes of ‘Faith, Hope and Charity’ and ‘The Holy Trinity’, to be the best windows he has made in Australia.

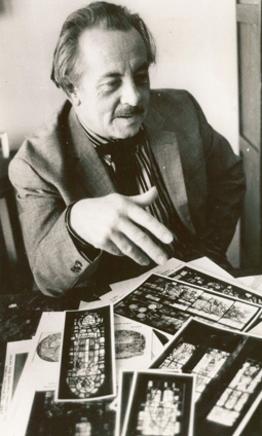

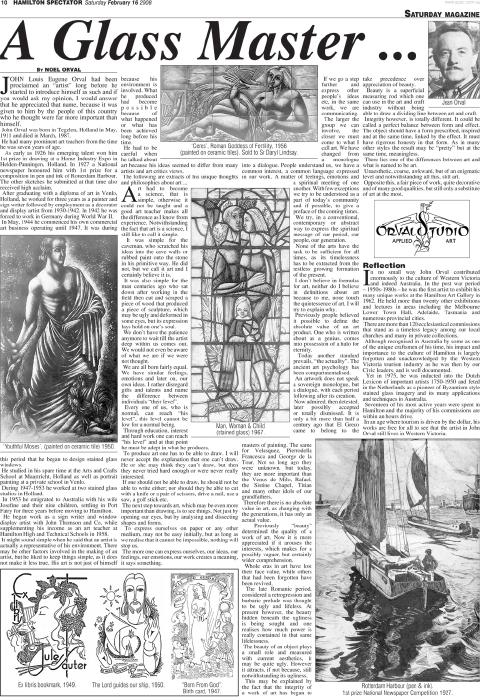

Jean with an array of photos of some of his commissions.

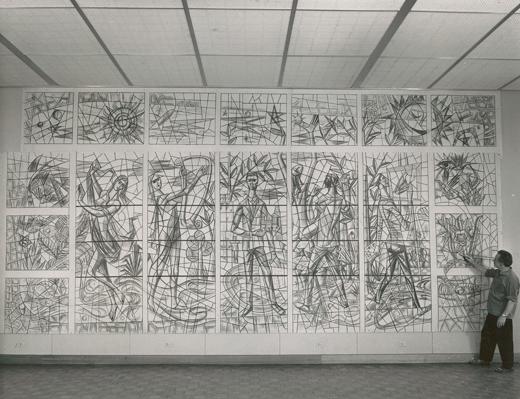

Hamilton City Council, in 1961, asked artists to tender for a major feature to adorn its Art Gallery.

Jean Orval's Proposals (one of which he is pictured with explaining to the Gallery Committee) was a wall of stained glass panels depicting local life and environment.

For reasons lost in time, City Council opted for an outsider's vision of the Greek mythical figure Prometheus.

How a copper statue drawn from pre-historic Greek culture reflected contemporary Hamilton life or history was never explained - and another opportunity for the community to benefit from the talents of a world renowned and local artist went begging.

The irony is that in the Greek classics, Prometheus is the Titan God of Forethought.

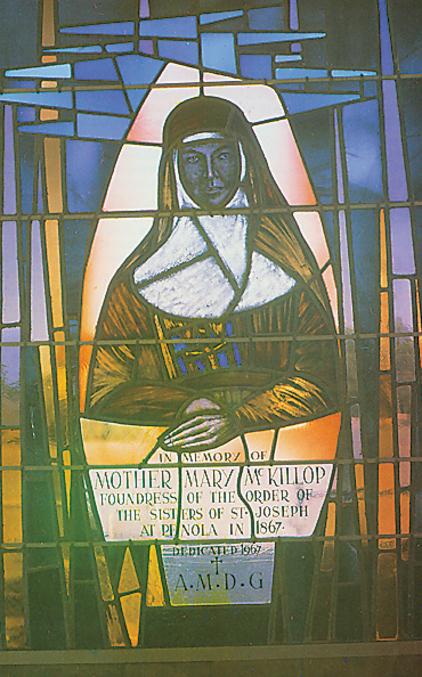

Mary Helen MacKillop (15 January 1842 – 8 August 1909), also known as Saint Mary of the Cross, was an Australian Roman Catholic nun who, together with Father Julian Tenison Woods, founded the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart and a number of schools and welfare institutions throughout Australasia with an emphasis on education for the poor, particularly in country areas. Since her death she has attracted much veneration in Australia and internationally.

On 17 July 2008, Pope Benedict XVI prayed at her tomb during his visit to Sydney for World Youth Day 2008. On 19 December 2009, Pope Benedict XVI approved the Roman Catholic Church's recognition of a second miracle attributed to her intercession. She was canonised on 17 October 2010 during a public ceremony in St Peter's Square at the Vatican. She is the only Australian to be recognised by the Roman Catholic Church as a saint.

Jean Orval was commissioned to create a portrait in glass in the porch of St. Joseph's Convent, Penola, South Australia.

Enhanced by the brilliance of morning light or the glow of a setting sun, the window - breathtaking in its aura of simplicity - was created by Jean Orval for the Convent's centenary in 1967.

This lifelike image of Saint Mary is an inspiration to the faithful. Perhaps now, belatedly, the artistry of a Dutch master of stained glass will also be "discovered" bringing the name of Jean Orval the universal recogntion of his talent that passed him by in his lifetime.

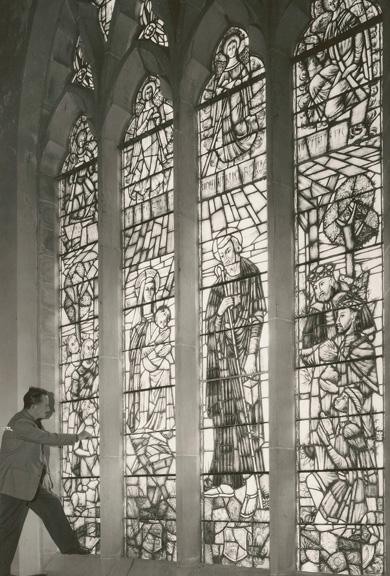

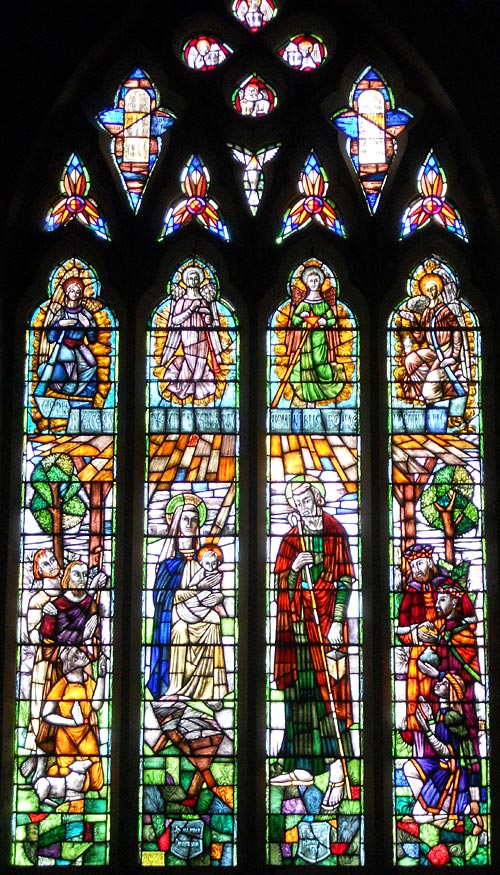

St Mary's Catholic Church, Hamilton, provided Jean Orval with his first major commission in Australia.

"The Nativity" is the large window between the entrances fronting Lonsdale Street and was installed in 1961. The window stimulated further design and production for other churches in Victoria and interstate.

The finished panels measured 21 feet by 10 feet, consisting of 2000 pieces of glass, 600 yards of leadstrips and 6 months of labour.

Jean is pictured below soon after the installation.

Works in the Hamilton Art Gallery

Archangel Gabriel

"The Expulsion"

Collection, Hamilton Art Gallery

Herbert Shaw Memorial Window

Collection, Hamilton Art Gallery

"Icarus"

Collection, Hamilton Art Gallery

"Glass Abstract"

Collection, Hamilton Art Gallery

Ron Lowenstern Memorial Window

Collection, Hamilton Art Gallery

Gouache

Collection, Hamilton Art Gallery

Jean's First Major Ecclesiastical Commission

Envisaged was a mosaic composition depicting life, labour and produce in the Western District.

AGRICULTURE

WOOL

INDUSTRY

COMMERCE

LIVESTOCK

John Jnr & Louis played an important role ...

On the many occasions of installation, it required the expertise

of Jean's son John Jnr to expedite the actual insertion of

church panels.

Being familiar with Jean's techniques and application of stained glass, John also played an integral part in the construction of his father's panels.

As a full-time employee through periods of the 1960s, John was the catalyst in ensuring the windows were erected and sustained purposefully in their housing, which sometimes required installing the panels at prodigious heights from a free standing ladder - something these days that would incur the wrath of the health and safety authorities.

John's considerable ability is still now testament to most windows being lodged in their original surrounds with little if any structural demands.

John's brother Louis was also a major support to his father and brought the knowledge and handiwork of his craft to further Jean's appreciation.

As with many of Jean's exhibitions, the sons were instrumental

in the transport and display of his works included in the

important role of accomplishing the required results

needed for future commissions.

This video depicts Jean, Phine and son Louis producing

a window for the Catholic Church in Mount Gambier,

followed by its installation.

Without Phine's unwavering support, Jean would not have continued through some of the disappointments that being an artist entailed.

Private Collection - Dunkeld, Victoria